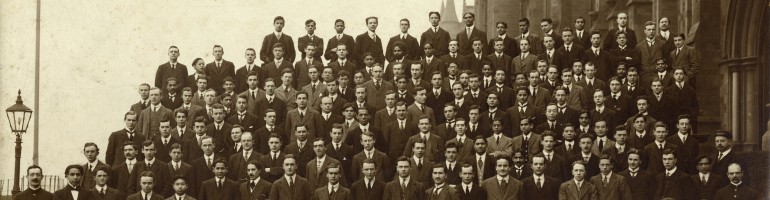

Scottish and German physicians in front of the ‘Führerschule’

It’s not like every German still breaks out into bitter tears when someone “mentions the war”, but it would also be wrong to deny the slightly uneasy feeling that makes itself felt when looking at primary sources from those years between 1933 and 1945. As an historian in the making, I am aware only a healthy critical distance allows us to shed a light into the darkest corner of our collective cultural memory. However, the perfidious propaganda of the National-Socialist Regime, their inhumane and ruthlessly efficient methods of annihilation, all the indescribable elements of evil of the Holocaust and the relative temporal proximity of the era present a grey area between intuitive emotional involvement, and the necessary critical distance to understand it.

When I started my work as an intern for the International Story Project, I had a hunch that researching connections between the University at which I studied, and Germany, the country where I grew up, would inevitably direct my research to this period. It was Kerry McDonald, who was head of the project, who first showed me the photo album that documented an excursion to Hamburg, Berlin and London made by the Glasgow University Medico-Chirurgical Society in 1936 (GUAS Ref. DC286). Looking at the photos, I was primarily trying to deduce from them the attitude with which 36 young men around my age were wandering through the Nazi-theme park that was Berlin in the mid 30s. The photos were, more than anything else, documenting a group of students on a trip to a foreign country and in that didn’t differ much from the standard photos tourists take of themselves immersing themselves in ‘local culture’.

The photo album was signed ‘Angus MacBeth Thomson’. Research at the University of Glasgow Archive revealed that he had been born in India, where his father was working in the Indian Educational Service. He was a student at Glasgow who had graduated in Science in 1934 and, at the time the photos were taken, was studying to become a doctor. He served with the Royal Army Medical Corps in India when war broke out Europe, and became assistant director of medical services in 1943. His career then took him back to the UK, where he became a distinguished professor at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. The visit to Germany had been organised by the Glasgow University Medico-Chirurgical Society, one of the oldest student organisations at the University.

Mr Thomson and his 38 compatriots embarked on their journey to Germany on the 21st March 1936. Berlin, the ‘Reichshauptstadt’, was just preparing for the propagandistic spectacle that was to be the Olympic Games. Removing all signs of anti-Semitism from the public eye to harmonise their urban image with the rules of tolerance and just treatment of the International Olympic Committee, the true aims of the Nazi party weren’t as evident to the observer as they would become a few years later. The delegation from the Glasgow University was taken to Germany’s broadcasting house in Berlin; to the Charité in Berlin, where they attended a demonstration of an operation; to the Führerschule der Deutschen Ärzteschaft (School of leaders for German physicians) in Alt-Rehse; to the labour camp and the mental asylum in Domjüch, Neustrelitz, which would become the sight of the systematic killing of the disabled and the handicapped under the codename ‘Aktion T4’. They were also taken to a political mass rally in the Deutschlandhalle, and, slightly bemusingly, to a production of Othello at the state opera house.

Berlin, 1936

In my endeavour to trace Mr Thomson’s steps back, to get a better idea of the nature of the excursion, I contacted historians and institutions in Germany in the hope of finding out who had initiated the visit. To my great fortune, research directed me towards Dr Stommer, art historian and project manager at the commemorative centre Alt-Rehse. I was then redirected to Dr. Hansson, research fellow at the Institute of Ethics and History of Medicine who had written an outstandingly interesting article on international exchanges at the institution in Alt Rehse, and is presently conducting research into the subject in collaboration with academics from Belgium, Sweden and Argentina.

Alt-Rehse, where Mr Thomson and the other students were accommodated after their visit to Berlin was the location of the Führerschule der Deutschen Ärzteschaft (School of leaders for German physicians). There has recently been a growing interest in the events that took place at the ‘Führerschule’ since, due to a lack of primary sources, not much is known about the eight years of its existence and what little is known has given rise all kinds of rumours. The school was built in the style of rural German country house in 1930s and was designed not only to produce physicians in this secluded spot, but to nurture them with National-Socialist ideology and cut them into the shape that would allow them to believe in the righteousness of the crimes they would one day commit in the name of the Vaterland. One quote from the text stuck with me in particular; it is a quote taken from the diaries of Johannes Peltret, second principal of the institution:

There is an old saying in my home country ;First see then believe.Germany is acting according to an even better principle: Illustrate to influence. You will all leave Alt Rehse with national socialism in heart and blood!

This quote, which illustrates the menacing perfidy of the National-Socialists’ educational endeavours perfectly, made me ask myself a question that presumably haunts everyone concerned with the era: how could the world not realise the consequences of the ideas the Nazis promoted? Why was it that many of them would let themselves be ‘influenced’ so eagerly?

While it becomes evident in the photos that Thomson was remarkably perceptive of National-Socialist propaganda around him, they also make the spectacle that was presented to them seem ridiculous in its grandiosity, laughable in its attempts to impress, and a matter of parody in its pedantry; “Charlie March looks for food while Hitler looks down” it says in the caption of a photo taken in Alt Rehse. “Der Führer and Dr Goebbels are doing some secretarial work” Thomson wrote under a photo showing two men on a train, their helmeted heads wafted by swastika flags. The combination of Tweed suits and Nazi-helmets suggests a role-play here. The caption beneath one of the photos in Berlin reads “Loudspeakers like lampposts along the road for relaying political speeches”.

‘The Führer and Dr Goebbels doing some serious secretarial work’

The impression one might get is that Scottish delegation was not exactly as awed or even impressed by the National-Socialist pathos as their foreign colleagues. However, the visit of the Medico-Chirurgical Society to Germany seems to be veiled in mystery, as all other mentions of discussions and articles on the subject seem to have been lost or never existed in the first place.

I would like to thank Dr Wilfried Stommer for giving me the first insights into the events at Alt Rehse, and especially Dr Nils Hansson for the article he sent me, without which I would have largely remained in the dark about international relations at the institution. I would also like to thank Kerry McDonald, whose knowledge fuelled my enthusiasm for the detective work we are doing at the archive, and without whose undying patience, advice and guidance, I would not have been able to find my way through the archives. I would also like to thank the team of archivists, who assisted me greatly in my work and made it a pleasurable and enriching work experience.

Much more work and time needs to go into research on the issue, so I hope that this is not yet the end of this article, but only an extended introduction.

________________________________________

References:

DC286/1 21 Mar-4 Apr 1936 Photograph album containing 76 prints of the Glasgow University Medico-Chirurgical Society visit to Germany and London held at the Glasgow University Archives

Hansson N, Maibaum T., Nilsson PM “Die ‘Führerschule’ in Alt Rehse: A Character School for the Physicians of National Socialist Germany” in Vesalius XVII, 2, 4, 2011, p. 4

Blogathon Entry by Klara Kofen, MA History, International Story Project Germany