With the Baton now having returned to the UK, we’d like to look back over some of the countries visited. Glasgow-based historian and PhD candidate Stephen Mullen, who kicked off the Commonwealth Caribbean project with a lecture on the Glasgow – West India connections, provides us here with a case study from his recent findings on some of the matriculating sons of merchants:

This article will shine a light on the life of University of Glasgow student Alexander Cuthill (also known as Cuthell) who – according to his matriculation record in 1786 – was the filius natu max: Adami Mercat: in insula de Jamaica. Thus, according to Addison’s magisterial account of students at Old College in this period, Alexander was the eldest son of a merchant on the island of Jamaica.

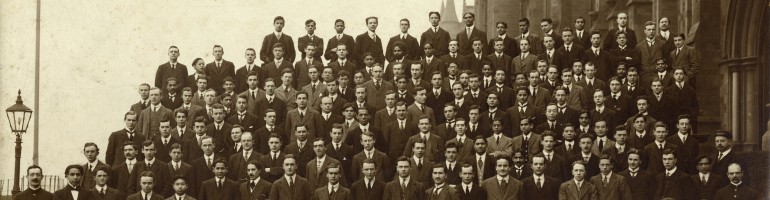

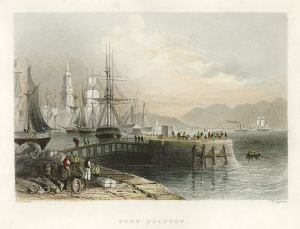

Alexander was part of a wider flow of sons of Scottish merchants and planters in the colonies who sought to give their offspring a prestigious education at Glasgow. One such student was Alexander Cuthill. His father was a Scotsman who travelled to Jamaica early in life and married a Scotswoman on the island. Alexander was born around 1772 and was described as a delicate child. At the age of 13 or 14, his parents sent him ‘home’ for education in the more temperate climate of Glasgow. What would the child’s reaction have been when he stopped off the ship at the Clyde?  How would he have acclimatised to an environment so far removed from his previous life? He would undoubtedly have found some friends after he registered for Professor John Young’s Greek class in 1786. Certainly, there were many other Jamaicans students there at this time. Many of them would have pursued commercial pursuits after a year or two at Old College, a general pattern amongst all students which was noted by a later Parliamentary commission in the 1820s. The location of Old College itself on the High Street – almost the commercial centre – also facilitated strong connections with academics and colonial merchants in local taverns. Adam Smith, for example, was friends with many ‘Tobacco Lords’ and was said to have taken much of his evidence for Wealth of Nations from a leading merchant, Andrew Cochrane. In 1786, merchants in the city were shifting commercial focus to the West Indies due to the collapse of the tobacco trade after the American War of Independence. Indeed, this period marked the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of the Clyde-Caribbean trade.

How would he have acclimatised to an environment so far removed from his previous life? He would undoubtedly have found some friends after he registered for Professor John Young’s Greek class in 1786. Certainly, there were many other Jamaicans students there at this time. Many of them would have pursued commercial pursuits after a year or two at Old College, a general pattern amongst all students which was noted by a later Parliamentary commission in the 1820s. The location of Old College itself on the High Street – almost the commercial centre – also facilitated strong connections with academics and colonial merchants in local taverns. Adam Smith, for example, was friends with many ‘Tobacco Lords’ and was said to have taken much of his evidence for Wealth of Nations from a leading merchant, Andrew Cochrane. In 1786, merchants in the city were shifting commercial focus to the West Indies due to the collapse of the tobacco trade after the American War of Independence. Indeed, this period marked the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of the Clyde-Caribbean trade.  The West India merchants of Glasgow were based at the Tontine Tavern at the Trongate – a stone’s throw from Old College – and Alexander would surely have been aware of the prominent citizens who paraded the ‘Merchant City’ in gaudy apparel, perhaps meeting them in taverns as he approached manhood. Alexander was part of the ‘plantocracy’ class and he may have been introduced to elite merchants after recommendations from his father. In any case, Alexander was destined to return to Jamaica in order to claim his inheritance – although with some reluctance it seems. He married a Scotswoman, Jean Wingate, in 1790 and the couple remained in Scotland some years.

The West India merchants of Glasgow were based at the Tontine Tavern at the Trongate – a stone’s throw from Old College – and Alexander would surely have been aware of the prominent citizens who paraded the ‘Merchant City’ in gaudy apparel, perhaps meeting them in taverns as he approached manhood. Alexander was part of the ‘plantocracy’ class and he may have been introduced to elite merchants after recommendations from his father. In any case, Alexander was destined to return to Jamaica in order to claim his inheritance – although with some reluctance it seems. He married a Scotswoman, Jean Wingate, in 1790 and the couple remained in Scotland some years. In the early 1800s, they travelled to Jamaica after a request from his father whom he hadn’t seen in around 20 years. Although Alexander has been described as the son of a merchant, in fact his father owned an estate. Given the economic structure of Jamaica in this period, this was most likely a sugar plantation cultivated by enslaved peoples. Alexander and Jean remained on the island several months, a period during which his father died. As sole heir, the son was able to take over the business of the estate which involved devolving management to a Mr Minto who had been appointed by Mr Cuthill senior. With the affairs ostensibly in order, Alexander returned to Scotland with no intentions of ever returning to Jamaica. He seemed destined to become the classic absentee plantation owner, living in luxury in Great Britain based on the profits of enslaved labour in the West Indies. However, the conduct of the attorney, Mr Minto, proved to be unsatisfactory and he had to be removed from the position. Accompanied by this wife as he was in a weak state of health, Alexander returned to Jamaica to remedy the situation although tragedy followed.

In the early 1800s, they travelled to Jamaica after a request from his father whom he hadn’t seen in around 20 years. Although Alexander has been described as the son of a merchant, in fact his father owned an estate. Given the economic structure of Jamaica in this period, this was most likely a sugar plantation cultivated by enslaved peoples. Alexander and Jean remained on the island several months, a period during which his father died. As sole heir, the son was able to take over the business of the estate which involved devolving management to a Mr Minto who had been appointed by Mr Cuthill senior. With the affairs ostensibly in order, Alexander returned to Scotland with no intentions of ever returning to Jamaica. He seemed destined to become the classic absentee plantation owner, living in luxury in Great Britain based on the profits of enslaved labour in the West Indies. However, the conduct of the attorney, Mr Minto, proved to be unsatisfactory and he had to be removed from the position. Accompanied by this wife as he was in a weak state of health, Alexander returned to Jamaica to remedy the situation although tragedy followed. In terms of death rates amongst British visitors, the West Indies were second highest after the Gold Coast and Sierra Leone in Africa and both regions were known as the ‘white man’s grave’. Jean Cuthill died in Jamaica before Alexander sorted the affairs of the estate. Having set sail for Scotland (probably around 1807) Alexander also died on the return voyage and a messy court case followed to divide up his considerable wealth at home. This short tale illuminates the life of Alexander Cuthill, before and after his short period as a student of Greek at the University of Glasgow.

In terms of death rates amongst British visitors, the West Indies were second highest after the Gold Coast and Sierra Leone in Africa and both regions were known as the ‘white man’s grave’. Jean Cuthill died in Jamaica before Alexander sorted the affairs of the estate. Having set sail for Scotland (probably around 1807) Alexander also died on the return voyage and a messy court case followed to divide up his considerable wealth at home. This short tale illuminates the life of Alexander Cuthill, before and after his short period as a student of Greek at the University of Glasgow.

To read more on Stephen Mullen’s ongoing research into Glasgow and the Caribbean , click on his Blog entitled ‘A Glasgow-West India Sojourn.’